Migration from Cambodia and the Domestic Labor Market

What is the typical profile of a potential migrant from Cambodia, and what are the drivers that lead individuals to migrate abroad? Recent research commissioned by USAID and carried out by EMC has attempted to answer these questions, and to investigate how one might address migration push factors that make it unattractive for vulnerable populations to remain in the country.

The majority of Cambodia’s migrants migrate through unsafe channels and without official travel documents, and are therefore at a heightened risk of people-trafficking. It is therefore crucial to better understand the profile of potential migrants and their motivations, in order to design development interventions that make migration safer, whilst also broadening the range of options that are available to them back home. EMC conducted interviews with over 900 potential migrants and 120 businesses in nine different provinces, and has published its findings in a report entitled Economic Targeting for Employment: A Study on the Drivers Behind International Migration from Cambodia and the Domestic Labor Market.

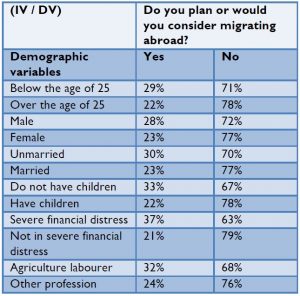

Statistically, those planning to migrate are above age 25, unmarried, childless, male, employed as agricultural wage laborers, and with an income that rarely covered expenses

Among other things, the study found that young, unmarried men from a low-income background are more likely to consider migrating abroad for economic reasons. Potential migrants have often incurred a significant amount of debt to pay for basic expenses like food and healthcare, and feel pressured to work abroad in order to repay their loans. In addition, climate events like drought and water shortages have made life more difficult for rural populations and act as a push factor towards migration. Although most push factors are economic in nature, the study found that financial distress can take several different forms, and that non-economic factors (like having a family network abroad) can have a catalytic effect on people’s decisions.

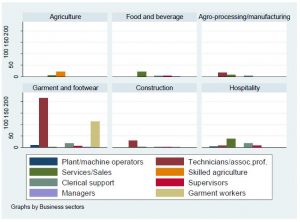

So what can be done to increase the options available to vulnerable populations in Cambodia? EMC found that there is significant labor demand within the country: half of the businesses surveyed reported difficulties in recruiting skilled and unskilled staff. However, businesses’ recruitment criteria were often not aligned with the skills and characteristics of potential migrants, a majority of whom have not completed school beyond primary level, and a significant proportion of whom have never attended school at all. It is therefore crucial to address skills shortages in collaboration with employers, government and technical/vocational training institutions, and to provide basic numeracy and literacy training. Much could also be done to improve information flow between employers and target populations regarding current job opportunities and required skill sets.

Almost half of businesses interviewed (46 percent) reported difficulties in recruiting staff members

There is nevertheless a persistent wage differential between the most labor-intensive sectors of the Cambodian economy (e.g. garment manufacturing and construction) and their equivalents in popular destination countries, like Thailand. These are not likely to be reduced in the short term, so a case should be made for institutional mitigation of risks associate with current migration practices. Efforts should also be made to reduce the financial burden of basic expenditure, such as food and medical costs, on low-income households. Such measures could go some way towards alleviating the human cost of economic migration, and buy time for policy-makers to address its underlying structural causes.

Migration can be a boon for low-income countries and migrants’ families, who receive remittances and benefit from the informal networks and skills that migrants obtain when they are abroad. The decision to migrate from Cambodia, however, has in the past been taken because of the limited livelihood options within the country, and despite significant risks to the migrant’s safety. EMC’s research is the latest contribution to the ongoing effort to improve the economic opportunities available to potential migrants, and to ensure that the decision to migrate is taken as an expression of economic freedom – to use Amartya Sen’s term – rather than being an inevitable consequence of financial distress.

Title Photo credit: Undocumented Cambodian migrants arrive by train at Anranya Prathet, Thailand prior to onward transportation to the border. © International Organization of Migration 2014, Joe Lowry.

Comments are closed.