Unlocking Cambodia’s Potential

Our report ‘Unlocking the Potential of the Cambodian Private Sector‘ has been published here. This study was carried out under the Mekong Business Initiative project (MBI). The MBI is a regional technical assistance project funded by the Government of Australia and the Asian Development Bank. This article is a summary of the report.

Cambodia’s economic performance has been strong for more than a decade, with real GDP growth averaging around 8% per year since 2001. Poverty rates have fallen, literacy and primary school enrolment have increased, and child mortality and maternal health have improved. Yet there is more to be done. With an inexpensive and young labor force, a strategic location in a fast-growing region, and a largely pro-business government, the potential for further inclusive growth is strong. This potential can be unlocked with the right reforms and support.

In general, Cambodia has a strong supportive institutional and policy environment for business. The Industrial Development Policy 2015–2025 (IDP) is the government’s “new economic growth strategy”. The policy aims for a structural transformation of the economy, from low-skilled to skill-based and technology- and knowledge-based. The policy is broad and ambitious but important if Cambodia’s private sector is to continue growing.

Cambodia’s private sector

Over the last two decades, the private sector in Cambodia has transformed the economy significantly. Employment has grown, although most people still live in rural areas where poverty and underemployment are highest. The education and skills of the labor force have improved, however many challenges remain (particularly for women; see here).

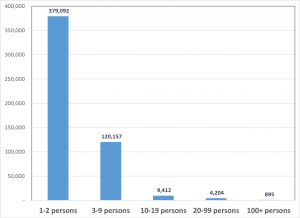

Most businesses are very small

Most private sector businesses are very small, and this causes problems such as high rates of informality. Smaller and informal businesses are less likely to be able to access finance, pay less (or no) taxes, and typically do not provide training for their workers or comply with labor laws and other regulations.

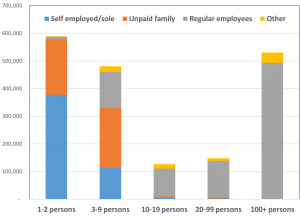

Most regular employees work in large businesses; micro businesses depend on unpaid family

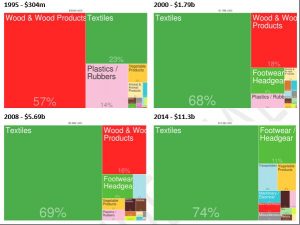

The Cambodian economy is more diversified than it was in 2008, although garments still dominate exports. The United States has become less important a destination. There is significant potential for more growth and diversification.

Cambodia’s Exports – Europe becoming more important, garments still dominate

Overcoming constraints on the private sector

Business surveys have long highlighted a number of constraints faced by the Cambodian private sector. Infrastructure constraints such as electricity and transportation are well recognized in Cambodia. One of the most-cited constraints is competition from the informal sector. Other major constraints reported by businesses include crime, corruption, business regulation, access to finance and labor skills. Not visible from business surveys is constraints created by the capacity of the businesses themselves. Problems such as weak corporate governance and low financial literacy can hold back the Cambodian private sector, and exacerbate other problems such as accessing finance or dealing with regulations and taxation.

Our report focusses on three constraints: business regulation, skills and education, and access to finance. Importantly, the IDP recognizes that these issues are preventing the private sector from reaching its potential.

Cutting red tape

Business regulation issues encompass business licensing and operating permits, customs and trade regulations, tax rates and tax administration, regulatory policy uncertainty, corruption, and anti-competitive and informal practices. A significant proportion of Cambodian businesses report that these are major constraints on their operations.

The government is aware of these problems and there are ongoing efforts to address them. Reforms of the tax system and streamlining of customs and trade-related administrative procedures have resulted in a significant decline of these barriers. In 2017, tax exemptions and incentives were introduced to ease the burden of firms transitioning into the formal tax system. However, formalization requires serious reforms in many areas, including customs and trade regulation, labor regulations, corruption, the legal system/conflict resolution, as well as taxation. Another main challenge in business regulation in Cambodia is its effective implementation, interpretation, and enforcement.

Skilling for the future

One of Cambodia’s assets is its relatively young and inexpensive labor force. However, over 40% of medium-size businesses identified an inadequately educated labor force as a major constraint. Companies report that there is a shortage of technical and vocational graduates relative to university graduates. One reason for this is that a university degree (particularly in social sciences) is much preferred by students and their families. The higher status of a university degree does not match the demands of employers.

Skills gaps and mismatches are linked to the access to and quality of education and skills training and to the priority (financing) government gives to different levels of the education system. Insufficient information provision and coordination with the labor market compounds the problem.

The underlying causes of Cambodia’s labor challenges are complex and interrelated. Unfortunately, there are few quick solutions. Long-term solutions will require reforms to the country’s education and training systems, as well as the provision of education and job market information to reduce skill mismatches.

Banking the unbanked

Access to finance is cited as major constraint by many Cambodian businesses. There are many reasons why. These include high rates of business informality, the inherent riskiness of lending to small businesses and farmers, low financial literacy, lack of suitable financial products, high collateral requirements, the difficulty banks experience in repossessing collateral following default, and the information asymmetries between borrower and lender that arise due to a lack of reliable financial statements.

It is important to evaluate the extent to which access to finance constraints arise from credit market imperfection that can be rectified or, alternatively, reflect an efficient financial system that is identifying and pricing risk appropriately.

Interventions to improve access to finance should address both the demand and supply side causes of this constraint. The IDP proposes a financing mechanism for SMEs and industrial activity. The details of this are yet to be determined. The costs and benefits of subsidized credit should be evaluated against matching grant programs and other financing options.

Problems such as weak governance can reduce businesses access to finance. Increasing the supply of educated entrepreneurs – people who can run productive businesses — will help the Cambodian private sector to be more efficient and dynamic, and such entrepreneurs are also more likely to create modern, registered businesses rather than inefficient, informal ones. Using business incubator services is one approach to raise business capability.

—-

These constraints are not new, and there have been some attempts in the past to address them. However, reform momentum has not always been as strong as it could. The IDP is an opportunity to re-energize the reform process, to address challenges that have been persisting for some time. The IDP has the potential to reinvigorate reform and elevate important, long-standing challenges to a higher level of government attention. It is an ambitious policy program and there is much to do for it to be a success to unlock the potential of Cambodia’s private sector.

Comments are closed.